OVERTURE

If a prime purpose of thinking and study and discussion and learning ends up as something like reasonable action that improves human life, then the overwhelming majority of SOP mediation that happens today in this largely intellectual and dialogic sphere is, viewed most optimistically, counterproductive and absurd. This assertion might appear quixotic and clearly makes a disputatious claim. However, this essay will contend that at least provisionally it proves that contention, in relation more exactly to broadcast or otherwise distributed discourse about social conflict that reputedly involves ‘race,’ ‘racial differences,’ ‘racism,’ and so forth.

In essence, because precisely one human race exists, ‘racism’ only addresses a socially developed concept about a false idea, that different races with different biological qualities in fact are a part of the human condition, a popular and yet completely incorrect conceptualization of human social relations that inevitably colors and distorts what happens among diverse social actors, probably in a completely toxic, and ultimately in a totally self-destructive, fashion.

This statement, inherently and indelibly, will likely effect strong feelings. Does a Spindoctor have the temerity to suggest that color is less important—than class or nation or other trait—as a key piece in understanding the social past? The answer, as the following initiation of this short monograph proves, would resound as an emphatic “No way!”

However, what we can make of that social import of coloration is still open to definition and interpretation. Before we continue to expound on such a task of delineation and elucidation, the sections just below offer readers a briefing about the rooted appearance and fuller manifestation of conflicted coloration during the current period of time.

Legacies of Slavery

Legacies of Slavery

A first point to make clear is that color did not always mean darkness, or diminution, nor did it ineluctably lead to an impunity to butcher and discriminate against those whose surface hues were dun or brown or charcoal. As a respected expert on Elizabethan culture quoted an even more venerated authority about Othello, “(she) situates the play ‘at a crossroads in the history of ethnological ideas when emergent racial discourses clashed with the still-dominant classical and medieval paradigms.”

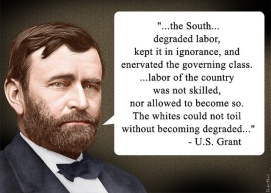

Those who follow along will see that point more fully in the coming preface. For now, we can aver that a primary legacy of slavery in the period of capitalism’s infancy was to overthrow most chances that dark skin under a bourgeois rubric could mean power or wealth or high station.

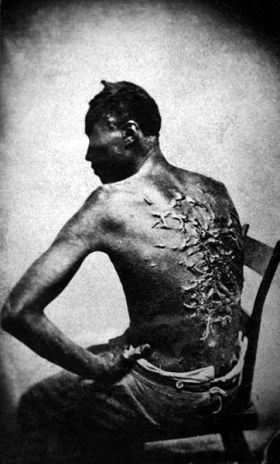

At least as much as any other correlative, the capacity to resist force against oneself or one’s friends or one’s family is a sine qua non of social potency. In the United States, the uncounted thousands of police and vigilante murders—and hundreds of thousands of assaults—each decade fall with such massive disproportion on people of color, and Black folk first among these assaulted populations, that any notion that chance determines this fate must look surreal. The very fact of the disparity is explosively ubiquitous at all compass points, both ideological and cultural, in mediated assessments from every possible place on our planet.

Rather than offering details on the panoply of recent men and women whom uniformed, militarized authorities have shot to death or otherwise slain, whether their surnames sound like Boyd or Brown or Crawford or Garner or Gray or Harris or Hicks or Hill or McKenna or Martin or Rice or Scott or Valencia—themselves part of an only casually tracked social set, over the past quarter century, of plus-or-minus tens of thousands of citizens cut down despite brandishing neither armament nor other credible threat against their killers—today’s analysis merely points out that a major disparity marks this population.

As many as three quarters of them descend from former slaves or ‘conquered’ peoples of the hemisphere, even though no more than a third or so of the overall population have such roots. Moreover, an even higher majority of the killers were Gringos of one stripe or other, and literally none of the ‘executioners’ who were Black ever dispatched a White person.

A fairly thorough search attempt, < “police killings” analysis OR detail OR history OR investigation comprehensive OR complete OR exhaustive OR list >, yielded almost two hundred thousand leads. Gawker and Mother Jones represent merely a pair of accounts from the first page that this pursuit of citations brought to the forefront.

The comments that accompany the latter article are an eruption of stress, tension, anger, and general defensiveness, with plenty of bigotry and blaming and name-calling mixed in. The lack of a context for dialog—which inherently must mean listening and respectful treatment—emerges with frightening clarity.

The mediated explanatory nexus, in any case—either as in these two articles a label, racism, or as in the case of other items among the hundreds of thousands of links a dismissal of color as a significant factor—guarantees that people cannot talk with each other about these matters. The ‘racist’ explanation, arguably, never moves beyond labeling, and overlooking the absolutely incontrovertible color-component either represents willful ignorance or unacknowledged prejudice.

By shifting the grounds of debate, by insisting that ‘police-involved killings’ look at slavery and empire, a different context for discussion might take place. In any case, further instances of color-coordinated violation and disproportion are easy enough to examine and portray.

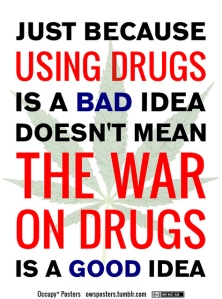

The carnage of the police state and the ghetto revolve inextricably around the war on drugs, which in many of its particulars echoes broader accounts of militarized assaults on citizens. The Spindoctor has written about these matters, establishing a template that allows subsequent analysis to highlight the way that ruling institutions—particularly military and ‘law-enforcement’—have subsumed roles that in earlier generations fell on masters and overseers and other enforcers of slave or colonial discipline.

The carnage of the police state and the ghetto revolve inextricably around the war on drugs, which in many of its particulars echoes broader accounts of militarized assaults on citizens. The Spindoctor has written about these matters, establishing a template that allows subsequent analysis to highlight the way that ruling institutions—particularly military and ‘law-enforcement’—have subsumed roles that in earlier generations fell on masters and overseers and other enforcers of slave or colonial discipline.

The American Civil Liberties Union summarizes this malicious and detrimental incongruity, irreconcilable with anything other than vicious injustice, double-dealing, and purposeful division: “Even though whites outnumber blacks five to one and both groups use and sell drugs at similar rates, African-Americans comprise: 35% of those arrested for drug possession; 55% of those convicted for drug possession; and 74% of those imprisoned for drug possession.

This skewed enforcement of drug laws has a devastating impact. One in three black men between the ages of 20 and 29 are currently either on probation, parole, or in prison. One in five black men have been convicted of a felony. In seven states, between 80% and 90% of prisoners serving time for drug offenses are black.

The statistics for the Latino population are equally disturbing. Latinos comprise 12.5% of the population and use and sell drugs less than whites, yet they accounted for 46% of those charged with a federal drug offense in 1999.”

Moving backward in time, the strict control or prohibition of slave drinking was common throughout colonial English and antebellum United States venues. That such restriction was never successful is not the point. Masters believed that prohibiting partaking would help to instill continued inhibition of license or other outrage. A suspected plan by slave seaman and workers to rise up in New York City and commit widespread arson and pillage was, in the estimation of prominent Whites, largely due to ubiquitous availability of unlicensed dram houses.

“Thus, whether or not there was an actual conspiracy to burn New York City in 1741, what is apparent is the central role drink and tavern life played for many slaves. Contrary to the advice given to British seamen, many northern slaves used

liquor as ‘a soother of the mind,’ a means to take their minds off the numbing brutality of their daily existence.And in contrast to the controlled settings of religious instruction, taverns and dram houses provided places slaves could socialize away from the prying eyes of masters and other whites.

Many whites agreed with the concerns expressed by (one) Philadelphian (master) that ‘the constant Cabals’ of slaves gathering ‘every Night and every Sunday’ could result in uprisings to the ‘great Terror of the King’s Subjects.’ (This trafficker in human chattel) believed that while sober most slaves would not go to the ‘desperate length’ of violent uprisings, but noted ‘how much they are addicted to Spirituous Liquor.’ With ‘little dram Shops [o]n every Corner and Alley,’ liquored-up slaves were described as acting with ‘great and uncommon impudence.’”

Just as, on any given plantation or in any forced-labor setting, an abrogation of abstemiousness and drudgery could lead to a brutal or even lethal thrashing or other retribution, or at least to steep fines or other economic sanctions, so too in contemporary arenas might the inherent human inclination to ‘get high’ reverberate in an African American life as granting to new ‘slave patrols,’ all clad in uniform blue, a license to discriminate, imprison, terrorize, or even murder the man and woman and child who express preternatural desires to alter consciousness or change their minds.

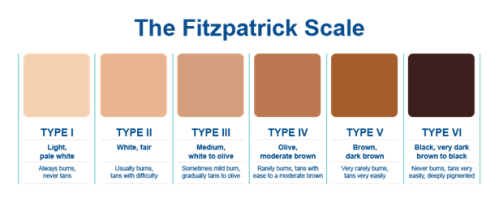

But these direct and all-too-frequently terminal attacks on brown bodies, and again especially in relation to African Americans, are not the deadliest form of destruction against those whose ancestors ended up being a mélange of slaves, slave masters, indigenous Americans, as well as others, all of whom we now lump under the collective descriptor of Black. On the contrary, the costs in morbidity add up to millions of years of impaired lives per annum as stress-and-poverty-related illness takes its toll in Black communities. The disparate mortality equally so taxes African Americans to millions of lost years in any given 365 day period.

Whether one tallies such illnesses as heart problems or cancer, kidney dysfunction or infectious disease, those whose ancestors lived in slavery suffer more. More grotesquely still, but congruently with the data on disease, the life expectancy of Black men lags behind that of White men by more than five years; Black women, meanwhile, experience three and a half years of lost life, on average, compared to White women.

These gross disparities in well-being are absolutely irrefutable. More or less a hundred million years of lost experience and consciousness is such a massive loss as almost to be incalculable. That Social Determinants of Health include color is no more arguable than that poverty kills. The annual toll of the negative impact of having great-great grandparents who toiled as slaves is, to say the least, a staggering waste, even as socioeconomic components almost always lurk behind these on-the-surface-very-visible issues of color.

Another insidious outcome, which often enough occurs in an even more vicious interpretive nexus, concerns Black families. Daniel Patrick Moynihan a half century ago authored a report for the Department of Labor. It couched its conclusions in an overarching concern for, and even solidarity with, the hopes and needs of ‘Negro’ people. Nevertheless, in terms of its managing its statistical data and in relation to its conclusions, the report without doubt placed the primary burden on Black ‘culture’ and ‘behavior’ as explanations for the inequalities and pathologies that were more and more prevalent in American cities ‘among the colored masses.’

A powerful critique of Moynihan began almost immediately, one that culminated in a thorough and often brilliant work. Blaming the Victim pushed back against the early erstwhile ‘Neoliberalism’ of the Department of Labor consultant. As the author, William Ryan, wrote, “My(original) memorandum and articles, along with articles by Benjamin Payton, James Farmer, and others, together with the activities of these and other leaders of the movement, temporarily derailed the Moynihan Report.” Such a phalanx of analysis needed no labels or jargon: scientific assessment disproved the superficially beneficent and insidiously harmful rhetoric and faux reasoning of The Negro Family.

But, as Ryan notes in disgust, despite all the necessary evidence to prove collusion and plan, sometimes “an ideology like Moynihan’s resonates to perfectly with the mood and purpose of the public and its intellectual leaders…that it is as hard to slay as the Hydra.” Before long, back in the sixties, and repeatedly since then too, “(s)ubsequent articles, reviews, and columns in Life, Look, The New York Times, and other influential publications supported and adopted the Moynihan thesis and swamped the opposition.”

The upshot, over time, was a ‘circling of the wagons’ among progressives to hurl  invectives against racism as the central way of assaulting this tendency. In the end, then, accusations of racist razzle-dazzle confronted solemnly fatuous pronouncements of Black irresponsibility. A more surreal juxtaposition is difficult to imagine. Such fallacious dualism ought to be below the level to which a clever twelve-year-old would cling.

invectives against racism as the central way of assaulting this tendency. In the end, then, accusations of racist razzle-dazzle confronted solemnly fatuous pronouncements of Black irresponsibility. A more surreal juxtaposition is difficult to imagine. Such fallacious dualism ought to be below the level to which a clever twelve-year-old would cling.

The alternative, after all, is both evidence-based and sound, capable of scientific instead of ideological assessment. Social replication of oppression and violence and murder, of prejudice and discrimination and injustice, led to horrific social consequences. One could, in establishing this immutable factual foundation, never conclude that the causal component was responsibility: always the issue would be upper crust benefit from consciously selected laws and policies and customs.

Under slavery, the progeny, both of slave lovers—generally unable to consummate marriage—and raped or seduced slave women whose pregnancies often did result from slave-owners, overseers, and their sons, became property that mostly the practice of the times was to sell to more or less far-afield plantations. One would struggle to find a more logically or morally repugnant position than contextualizing such predation as irresponsibility by slave fathers and mothers.

So too, today, and in other situations between then and now: most contemporaneously, African-American children come into the world in communities where one half or more of the fathers end up missing because of a system that feeds off their labor and targets their behavior, indistinguishable from that of Anglo-Americans, in such ways as to incarcerate and disfranchise and impoverish them for life. Again, a less reasonable and civilized nexus for rearing children is tough to dream up, so that to blame Black families and communities in such a context is, at best, noisome and moronic.

The nauseating and idiotic, illogical and immoral elements of the establishment arguments, though, somehow do not end up the endpoint. The climax instead comes down to racism.

In essence, therefore, this debate, which monopoly-media’s multiple tentacles unvaryingly describe as a racial matter, either a display of racism or a sign of race-neutrality, itself is a legacy of slavery. That most outlets, even the so-called ‘liberal’ or—heaven protect us—‘leftist’ ones, use sophisticated and frequently sophist argumentation to bolster Moynihan ought to be an expected outcome. And, meanwhile, everyone who gets to come to the podium is talking about ‘race.’

An only months-old article in New Yorker, which also brings the estimable Orlando Patterson into the fray, is a good example of such a propagation of propaganda. With a few radical or Marxist exceptions, critics of this and other establishment paragons do not frame the issue as the falsity and error and distortion that are omnipresent in such work; nor do the policies and objectives of the falsifiers ever become the prime locus of controversy; rather, everything comes down to pointing fingers at racist beliefs, which stand as the sole sorts of rebuttals to the heartfelt remorse for immaturity and negligence and so on that typify the Moynihans of the world.

Though the Spindoctor would welcome the opportunity rigorously to dispute and deconstruct those who would defend Moynihan’s theses and use of evidence, this is out of the scope of today’s article. Instead, readers here need only understand the possibility that the characterization of the New York thinker’s followers as racist may itself promote outcomes that further inequity and disproportion, in other words that are racist in their results. Instead of this, one may at least want to ponder a more political-economic, historical, and social dynamic for negotiating these complex and difficult thickets of America’s past and present.

One might in essence detail every possible sign of social health or social ill, and one would discern the impact, through intermediating decades since the 1860’s, of the murder and mayhem and impoverishment and outrage of chattel slavery on the contemporary experience of Blacks in the United States. In any portrayal of wealth, status, certification, on the one hand, and neurosis, psychosis, violence, and on and on and on, ad infinitum, on the other hand, the inheritance of four or more centuries of enslavement colors the lives of African Americans in the 21st century.

Orlando Patterson, in his Slavery & Social Death, unfurls for his readers the imposition of the erasures that chattel relations elicit as intentional effects of systematic involuntary servitude. This dialectic, of exploitation and denigration, even though it has always exploded in the owning classes’ faces, is universal, as Patterson and others show in relation to Southern Europe and the Mediterranean, in regard to Japan and Korea in Northeast Asia, and in terms of every nation that grew out of Spain’s and Portugal’s conquest of most of South America and the Caribbean.

Yet these diverse loci of human ownership of other, often but not always differently colored, people is seldom—and in the mass media or corporate journalism the descriptor is basically never—a topic that those who propose to explain current events explore. While to delve even minimally in this arena right this second would be unsupportable, must in essence await a contract or something similar for a three-to-five volume series, a less-than-minimal peek at one of these other instances of slavery could be suggestive.

For this purpose, a glance at the plight of Roma peoples can certainly serve. Interestingly enough, the Romanian period of enslavement very closely parallels what transpired in North America. Plus or minus four centuries of slave-relations came to an end around 1860, yet social horror—disproportionate difficulty among Roma communities and horrid discrimination and intolerance against Roma citizens—has continued through the present, not only in Southern Europe but throughout most of the Eurasian landmass.

“The difficult situation of the Romani population in Europe has recently attracted widespread attention. The collapse of communism in Central and Eastern Europe brought with it the demise of state welfare measures and, simultaneously, the end of official pressures for enforced assimilation–suddenly leaving Romani communities there to fend for themselves in a new, uncertain, and often hostile world.

Responding to this quandary, numerous governments, international organizations, foundations, nongovernmental organizations, and, most important, Romani leaders themselves are trying to devise programs and policies to address the deep and complex problems of discrimination and poverty that so disproportionately affect the Roma.”

The legacy of slavery, therefore, both in the United States and elsewhere, hypothetically comes down to centuries of brutalization, demonization, and exploitation long after protest and struggle have sundered the explicit chains of bondage. The upshot is the reimposition by alternate means of the imprimatur of ownership and conquest. The ultimate outcome is the universal attempt to degrade the oppressed and demeaned, which serves to salve the psyches of rulers themselves and to malign the ‘lowest of the low,’ and ‘the blackest of the black,’ from others whom elites need to control and manipulate to hegemonic ends.

Legacies of Colonial Empire

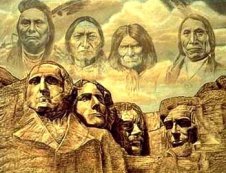

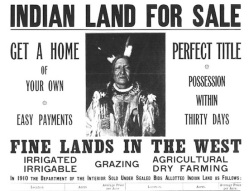

No set of relations which emanated from the English colonies and the United States came closer to a completely ‘successful’ genocide, of course, than did the calculated mass homicide of indigenous peoples. Since the present-day assault on Native American individuals is less immediately apparent in journalistic or scholarly mediations, readers may rest easy that a more succinct summation is imminent now.

To provide an overview, one cannot turn to a better choice that the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. John Marshall had in many ways been both a promoter of consolidated elite rule and of color chauvinism in his early career. In 1823, he issued perhaps the most damning and important opinion of a career that in many ways completely defined a ‘balance of powers’ that was anything but.

In this case, Johnson and Graham’s Lessee v. Macintosh, speaking for the majority, Marshall candidly laid the foundation for a pointed and comprehensive dismissal of any idea that Native inhabitants of the Americas might share even approximately equivalent rights as residents of European ancestry. From the Atlantic to the Mississippi, the only rule was of European interlopers, maintained by force of arms. He did not blame either party to this continental conflict, but the victors’ ultimate imprimatur was, despite the facts of interbreeding which he assiduously denied, unquestioned, unquestionable, so that ‘public opinion’s’ softening of harsh rule was not at issue.

After all, from the American ruler’s high bench he could allege, “the tribes of Indians inhabiting this country were fierce savages whose occupation was war and whose subsistence was drawn chiefly from the forest. To leave them in possession of their country was to leave the country a wilderness; to govern them as a distinct people was impossible because they were as brave and as high-spirited as they were fierce, and were ready to repel by arms every attempt on their independence.

What was the inevitable consequence of this state of things? The Europeans were under the necessity either of abandoning the country and relinquishing their pompous claims to it or of enforcing those claims by the sword, and by the adoption of principles adapted to the condition of a people with whom it was impossible to mix and who could not be governed as a distinct society, or of remaining in their neighborhood, and exposing themselves and their families to the perpetual hazard of being massacred.

Frequent and bloody wars, in which the whites were not always the aggressors, unavoidably ensued. European policy, numbers, and skill prevailed. As the white population advanced, that of the Indians necessarily receded. The country in the immediate neighborhood of agriculturists became unfit for them. The game fled into thicker and more unbroken forests, and the Indians followed. The soil to which the Crown originally claimed title, being no longer occupied by its ancient inhabitants, was parceled out according to the will of the sovereign power and taken possession of by persons who claimed immediately from the Crown or mediately through its grantees or deputies.”

Power and victory, swords and sway, Marshall does not once mention race in the opinion, nor need he. The historical underpinning is one of political economic plunder and social evisceration that may or may not ever necessitate compensation of any sort, let alone remuneration, or even a semblance of mutuality. Again, indeed, “(h)owever extravagant the pretension of converting the discovery of an inhabited country into conquest may appear; if the principle has been asserted in the first instance, and afterwards sustained; if a country has been acquired and held under it; if the property of the great mass of the community originates in it, it becomes the law of the land and cannot be questioned. So, too, with respect to the concomitant principle that the Indian inhabitants are to be considered merely as occupants, to be protected, indeed, while in peace, in the possession of their lands, but to be deemed incapable of transferring the absolute title to others. However this restriction may be opposed to natural right, and to the usages of civilized nations, yet if it be indispensable to that system under which the country has been settled, and be adapted to the actual condition of the two people, it may perhaps be supported by reason, and certainly cannot be rejected by courts of justice.”

Today, one result of this foundation is that so-called Indians have in many jurisdictions the lowest life expectancy of all ethnic groups in North America. In many cases, their time on Earth compares to that of the citizens of nations with only a fraction of the wealth of the United States.

The most troubled evaluations of self show up in limited studies of cohorts of young Indian men and women as well. Higher rates of depression, double or triple or higher rates of suicide, and other such indicia are commonplace.

The highest levels of illiteracy, of alcoholism, and of other social dysfunction are also frequent “on the res.” These difficulties extend from Alaska to Florida, from California to Maine.

Casinos must in some way represent a perverse dialectical punctuation of this entire process. Here are Indian establishments where retired gringos and well-heeled Anglo fools drop billions of dollars every day. To what end remains uncertain, but the ironic nutrients of such soil must tantalize the storyteller.

Whatever the ultimate assessment of this odd twist might be, the abandonment of Native American communities and the consignment of these ‘Red’ peoples’ bodies to history’s dust-heap remains still the default position of the Bureau of Indian Affairs and other institutional repositories of hegemony. Nonetheless, these inhabitants who ‘owned’ the continents of this hemisphere until conquest robbed them of their birthrights, having come the closest to extinction, now have manifested powerful proponents of recompense, an American Indian Movement and other propositions that parallel in many ways the work of Huey Newton, Malcolm X, and others among African Americans.

While no nation practices with such thorough arrogance as does the U.S. its war against duskier-skinned original inhabitants, this pattern of discriminatory rough treatment characterizes almost all of Europe as well, both at home and in the outposts of ‘Commonwealth’ and such. Furthermore, and to the nub of what today’s material concerns, the universal accounting for this oppression of ‘native’ folks is that racism is in play.

As above, a future comparative analysis of these matters might better illuminate what is happening in different local settings than does the light cast from more focused study. No matter what, though, one need not rely on ‘racial’ rationale to account for what has come to pass. Justice Marshall’s opinions resonate powerfully without making such opaque and poorly classified terminology the fallback position.

Legacies of Civil War, Reform, & Reconstruction

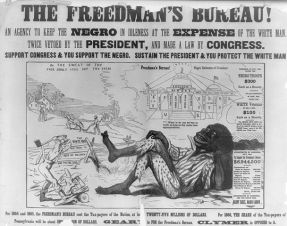

Again focusing on the U.S.A., distrust is a widespread result of the way that, after African Americans played instrumental roles in conquering the slaveocracy in the South, the Union reneged on its promises—forty acres and a mule were out of the question when not even a franchise and protection of free labor were possible—and reintegrated former Confederate elites back into their accustomed positions of preeminence. Such treachery made the deepest sort of mistrust unavoidable.

As Melissa Williams makes the case, “(t)he Black political experience during

Reconstruction tells the story of trust given and trust betrayed.” As Professor Williams delineates in her mixture of political philosophy and history that she applies to the here-and-now, this bad faith has persisted till the current moment, a lingering sore that emanates from opportunistic politics and calculated profiteering that also continues to define the present pass.

While a researcher could develop volumes on this issue, a verse from a song in the Dead Prez compilation, Let’s Get Free, can serve for now. This is from the track, “The Animal in Man,” which tells the story of George Orwell’s Animal Farm as an admonitory parable of U.S. society, in which the ‘disgust and betrayal’ might readily refer to the lionization of Lincoln and Civil War in light of what followed.

“After they ran the farmer off the farm

The pigs went around and called a meeting in the barn

Hannibal spoke for several hours

But when talks about his plans for power

That’s when the conversation turned sour

He issued an official ordinance to set

If not a pig from this day forth then you insubordinate

That’s when the horses went buckwild

One of them shouted out

‘You fraudulent pigs, we know your fucking style!’

Hannibal’s face was flushed and pale

All the animals eyes full of disgust and betrayal

He felt the same way (Farmer) Sam felt

They took his tongue out of his mouth

And cut his body up for sale, for real

You better listen while you can

Its a very thin line between animal and man

When Hannibal crossed the line they all took a stand

What would have done?

Shook his hand?

This is the animal in man.”

In such an overall milieu, calls for reparations have become more insistent over the past few decades. They make most Whites want to puke, of course, at least stateside. The reasons for this distaste, even though the Spindoctor supports the concept of community-based remuneration for past injustice, are not ludicrous. The most interesting potential of such actions is that they can elicit intercourse between parties that would basically never otherwise talk with each other.

Readers may discover much more about this topic in a future essay, but for now, a snapshot of what happened in a Duke University forum in March, 2015, might help a thoughtful student of these matters put things into perspective. “Like Coates’ piece (a year ago in The Atlantic), the conversation at Duke centered less on the who, what and how of reparations and more on why reparations are needed. In their remarks, panelists expressed cynicism that reparations would come to pass in their lifetime or even in the next few generations, but also hope for how even just a serious national conversation about them could transform—or, to use a panelist’s word, ‘redeem’—America.”

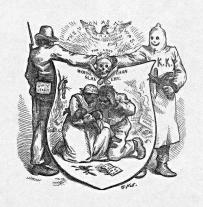

Related ‘truth-and-reconciliation’ processes also are an aspect of what some community leaders suggest could play a part in healing and integration. In November, 1979, with the advance knowledge of various police forces, heavily armed fascist assassins targeted and murdered communist and grassroots activists who were helping to organize workers into unions and community groups in Greensboro, North Carolina.

This event permits a deep insight into the forces at play in situations where color and class and empowerment collide with reactionary forces that will go to any length to prevent social progress. Of the hundreds of participants in the rally that turned into a killing field, over ninety per cent were African American. Of those whom the Klan and Nazi hit-men shot to death, four of five were White. All five were members of the Maoist political group that had organized the rally against the Klan, one of dozens of actions in the mid-to-late-1970’s, of which the humble Spindoctor organized one and argued passionately not to encourage “Death to the Klan” chanting or publicity of the sort that were bedrock aspects of the Greensboro slaughter.

In Greensboro, “The KKK and Nazi members shot at anyone who wasn’t hiding while four television news teams and one police officer recorded the action. They then got back into their cars and sped away after which the Greensboro police arrived and began arresting protestors.

In the aftermath five people were killed and 11 wounded in the attack. All five were members of the Workers Viewpoint Organization (WVO), and four were rank-and-file union leaders and organizers.” Despite the intentional murder or involuntary manslaughter on display, not one of the shooters ever served a day in prison for this charnel dispatch of white organizers.

In a move that many radicals have criticized but which did in fact help to provide clarity and a platform for vocalizing rage and longing in regard to this brutal mass homicide, Greensboro created a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to do something about the rifts that the occurrence created in the city. “The truth and reconciliation process is designed to examine and learn from a divisive event in Greensboro’s past in order to build the foundation for a more unified future. The Greensboro Truth and Reconciliation Commission is based upon similar efforts around the world, most notably in South Africa. Building on this wealth of international experience, Greensboro represents the first application of this model in the United States.”

While these and other stabs at reformulating resistance and reimagining integration very often embrace the very social forces that most profited from the original bondage and exploitation, just this sort of contradiction implies a polarity from which dandy dialectical dances might emerge. In any event, by placing the discourse on a plane of equality and reason, they make possible conversation that is utterly independent of racial thinking, put-downs about racism, and so on and so forth.

The resuscitation of the slaveholding classes almost a hundred fifty years ago, simultaneously as the non-owning Whites served again as whipmasters and enforcers against former chattel, echoes in every police department that ‘serves’ an eighty-percent Black community with a four-fifths European American Gestapo. Thus, the need for remediation not only stems from relatively long-ago wounds that have festered and never healed, but also from dynamics of inequity and injustice that explode anew on the contemporary scene.

To rectify the past could be, in a sense, to rejuvenate the present thereby. The devilish details of such possibilities, in and of themselves, establish the boundaries for a discussion that could bring together social forces otherwise seemingly intractably opposed.

Once again, a Spindoctor with a license and a budget could go off while he kept going on here. These attempts both to express a networked engagement and seek a wider hearing for redress are only possible because a more civil society has to some extent actually come into being; at the same time, unfortunately, in the vein of ‘one step forward, and two steps back,’ the threat of backsliding is ever present.

As in every case in this essay—and in many of the other such analyses that the Spindoctor promotes—the standard-operating-procedure has been to consider events in ‘America’ first, since, if nothing else, they are easiest for him to investigate. In fact, however, even in this instance of what seems a ‘uniquely’ Yankee process, one might turn to Russia or British India or many other places on the planet to see similar processes in play as have resulted today in the U.S. from Civil War and reconstruction.

A freshly minted news analysis from Counterpunch takes note of a tricontinental strategy session on the topic of reparations that took place in New York early in April of this year. Contingents from the U.S., Latin America and the Caribbean, and Europe all met with the intention to establish networks and develop a strategic orientation that would allow activists to demand and attain compensation for serving so long as prey for the howling wolves of imperial finance and industry.

“French reparations activists have filed lawsuits and initiated other actions around reparations from deprivations by France in the Caribbean and in Africa. CARICOM nations have established a Reparations Commission to conduct further research to initiate legal and other actions against governments of Britain, France and other European countries that maintained colonies in the Caribbean basin.

Louis-Georges Tin, an anti-racism and reparations activist in France, said he had travelled to the Summit with a delegation from the European Reparation Commission to establish closer connections with other reparations activists.”

In a wider parsing of these sorts of skirmishes, one can posit that a primary thread of fascism, in every case since Italy, has interwoven with the expression of the insistence that newly freed slaves, serfs, indentured populations, colonial citizens, and so forth receive a boost for having for decades or centuries confronted exploitation and violent violation. The aristocratic thugs who have most suffered the loss of their privileged position at the ‘top of the heap,’ and easily recruited petty bourgeois sorts who crumble in every crisis, combine and demonize these ‘lower races’ as worthy of renewed depredation.

Legacies of a New Imperialism, Orchestrated from Washington by ‘Free Trade’

In no other arena is the ultimate sinister inheritance of the present historical eventuality worse than in the almost innumerable cases of the rising, and now fully risen, American leviathan’s now planet-spanning neocolonial, neoimperialist enterprises—almost always cast as liberation and aid, as if death and destruction and profiteering and plunder were the result of loving and friendly impulses. Furthermore, because of the inevitable realities of the historical synthesis of these ventures, whether one examines the Philippines or Honduras, Nigeria or Bangladesh, ‘colored people’ still bear the ugly brunt of the ugly American and his beautiful machinery and other machinations of capital’s sway.

The repercussions of this dynamic universally enable vast, seemingly interminable killing and chaos. Looking at a map of the world with overlain graphics of contemporaneous war and social upheaval, this is of course obvious. But in a sense similarly as the Wicked Witch ruminated in The Wizard of Oz, the how of these horrific tortures’ unfolding, again and again with the United States of America in the role of lead executioner and chief puppeteer, is a riddle that study and explication must figure out, unless some sort of random sadomasochistic thrill attends the continuation of these chaotic catalysts of violation and violence.

In an earlier incarnation, the Spindoctor wrote about these matters in relation to  the connection between present-day assaults on ‘illegal immigrants’ and two-century-old attacks on Native Americans. “These days, along I-20 from Atlanta to Birmingham, State Troopers seek out ‘illegal immigrants,’ trying to catch and eject them from ‘America.’ Eighteen decades ago, along substantially the same route, the leaders of Georgia—who had recently inaugurated the country’s first ‘Gold Rush’ in Dahlonega–and Alabama—who were readying river valley properties for slaves to work–were preparing to throw out local native inhabitants so that the conquering European immigrants could do whatever they liked. Those who like ironic history will love today’s story.”

the connection between present-day assaults on ‘illegal immigrants’ and two-century-old attacks on Native Americans. “These days, along I-20 from Atlanta to Birmingham, State Troopers seek out ‘illegal immigrants,’ trying to catch and eject them from ‘America.’ Eighteen decades ago, along substantially the same route, the leaders of Georgia—who had recently inaugurated the country’s first ‘Gold Rush’ in Dahlonega–and Alabama—who were readying river valley properties for slaves to work–were preparing to throw out local native inhabitants so that the conquering European immigrants could do whatever they liked. Those who like ironic history will love today’s story.”

Incongruities of this sort, at once bizarre and darkly humorous, abound in the imposition of U.S. imperial authority. The Philippines is a good example. Although U.S. rulers positioned their forces as liberators, almost before the Yanks had run the Spanish off, the Moro and other local Filipino freedom fighters had turned against Uncle Sam and his minions.

“This was not the first time that the United States had dramatically expanded its territories. Neither was this the first time that it had done so by war with another nation (Mexico, 1846-48). That this expansion required the violent subjugation of nonwhites (in this case Filipinos, but for much of the same century, Native Americans) was hardly new, either.

Nevertheless, ironies of empire abounded for this self-styled democratic republic. Many of these ironies were scathingly noted by American anti-imperialist Mark Twain in his writings. Critics pointed out the irony of fighting to free Cubans from Spanish colonial rule then fighting the Filipino War (1900-1902) to retain colonial dominion over a captive people.”

Furthermore, this mismatch between rhetoric and reality—in which prostitution and graft and thuggery accompanied high-finance and ‘foreign aid’ and ‘development loans’ that seemed to make people poorer and hungrier while well-fed American soldiers watched over things throughout the region at facilities like Subic Bay–continued through the closing of the huge base near Manila and persist even as only occasional visits of naval flotillas now occur.

Central Africa, with its mosaic of murderous machinations of British and French and Belgian malediction, would hardly seem like a realm where U.S. malfeasance reigned supreme. However, in the aftermath of the colonial collapse, a new mechanism for control emerged, in which Central Intelligence Agency and corporate functionaries replaced old-school bureaucrats and aristocratic sociopaths.

Thus, from the well-tuned machinery of assassination that sucked up and spit out Patrice Lumumba and countless others to the coordinated management of mass mayhem that characterized the events of Hotel Rwanda and more, the integrated circuitry of exploitation and control has held sway in this region and throughout the ‘dark continent.’ That ‘race’ was comparatively unimportant in these ministrations of horror is possible to demonstrate: after all, numerous recent retrospectives on the ten years of Vietnam’s agony show similar patterns and goals and outcomes as what happened in Africa, or for that matter in Chile forty-two years ago, the Whitest country in Latin America.

Thus, from the well-tuned machinery of assassination that sucked up and spit out Patrice Lumumba and countless others to the coordinated management of mass mayhem that characterized the events of Hotel Rwanda and more, the integrated circuitry of exploitation and control has held sway in this region and throughout the ‘dark continent.’ That ‘race’ was comparatively unimportant in these ministrations of horror is possible to demonstrate: after all, numerous recent retrospectives on the ten years of Vietnam’s agony show similar patterns and goals and outcomes as what happened in Africa, or for that matter in Chile forty-two years ago, the Whitest country in Latin America.

In many cases like those above and in relation to Yemen and throughout the ‘Grand Chessboard’ of much of Southwest Asia and the Horn of Africa, the United States has in some views shouldered the “White Man’s Burden.” Kipling’s poem was explicitly about enlarging the scope of U.S. dominance and creating a web of Anglo-American rule over all the lesser, darker folk of the planet, albeit for their own good.

How could such lines as these not be racist?

“Send forth the best ye breed—

Go send your sons to exile

To serve your captives’ need

To wait in heavy harness

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught, sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child…”

The answer to that query, if one is willing to listen, is threefold: the lyrics of Gunga Din; the repeated, ad infinitum, carefully plotted murder of the best and brightest and dearest of these “sullen peoples” because they dared oppose capital; and the occasional early and now almost constant deployment of other “sullen peoples” to control the initial beneficiaries.

In such a context, ‘race’ offers no more clarity than voodoo as elucidation. The key issue of who the conquerors actually recruited locally is also centrally important, about which more directly.

In this new kingdom of bourgeois property triumphant, over time, no place has been off limits to the American Century’s imposition of dominance. Racism is a convenient label that explains none of it, as this preeminent hegemony of the ‘American Way’ has spread out in all directions.

Readers may refer to material just above for a reference to Cuba, Westward across the Atlantic. The Spindoctor has mentioned the island’s history and revolution both here on Contributoria and in earlier writings. Cuba’s resistance to U.S. depredation is a testament to a non-racialist social system. Nevertheless, despite decades of rejuvenated Latino empowerment, in part because of Havana’s successfully standing up to Washington, the threat powerfully persists in Latin America of further slaughter that the Gringos orchestrate.

The network of this dictatorial dominance presumes to encompass everywhere on Earth, including Moscow and Beijing and Tokyo and Berlin and London and Paris. Whether this nearly completed fantasy of a Reich eternal in fact summarizes the human condition may well turn on the capacity to impose a ‘racialist’ mindset on those who protest imperial victory, where the day-to-day operations of ‘business as usual’ lay the groundwork for ghettoes and concentration camps.

Thus, just as in the United States proper, so too in the grinding operations of far-flung provincial and metropolitan dynamos, this systematic mass murder does not lead to the greatest injury and loss and destruction. In the present parlance, ‘Economic Hit Men’ do substantially, or even vastly, greater damage than do the relatively brief interludes of homicide and mass slaughter.

The World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, and other ‘partner’ institutions eviscerate the so-called Third World. Corporate protocols—in arms trade, in relation to ‘medicine,’ in the energy sphere, in technology—further these patterns of dependency and despond. Again, the critic’s response blames the IMF’s or Apple’s or Chevron’s racism, as if any strategic rejoinder to the anaconda of monopoly finance is possible as a result of such a view of victimization and vengeance.

All such sociopolitical developments, with their very specific and well accounted for political economic results, depend on willing cretins from the ‘free polities’ in question, whose service to imperial interests is no more in doubt than are the trade balances that happen when extracted minerals stack up against automatic weapons and sophisticated telecommunications and electronic control methodologies. Franz Fanon is just one brilliant annalist who documents these matters, particularly in relation to North Africa. He speaks hopefully of a revolutionary dialectic that goes beyond ‘development’ that mirrors the West.

“So, comrades, let us not pay tribute to Europe by creating states, institutions and societies which draw their inspiration from her.

Humanity is waiting for something other from us than such an imitation, which would be almost an obscene caricature.

If we want to turn Africa into a new Europe, and America into a new Europe, then let us leave the destiny of our countries to Europeans. They will know how to do it better than the most gifted among us.

But if we want humanity to advance a step farther, if we want to bring it up to a different level than that which Europe has shown it, then we must invent and we must make discoveries.

If we wish to live up to our peoples’ expectations, we must seek the response elsewhere than in Europe.

Moreover, if we wish to reply to the expectations of the people of Europe, it is no good sending them back a reflection, even an ideal reflection, of their society and their thought with which from time to time they feel immeasurably sickened.

For Europe, for ourselves and for humanity, comrades, we must turn over a new leaf, we must work out new concepts, and try to set afoot a new man.”

And he also decries those who sell out the oppressed among their people, the workers and peasants and common folks. “To its brutal policy of oppression(the colonial administration) adds a spectacular and judicious combination of détente, divisive maneuvers, and psychological warfare. Here and there it endeavors to revive tribal conflicts, using agents provocateurs engaged in what is known as countersubversion. Colonialism uses two types of indigenous collaborators to achieve its ends. First of all, there are the usual suspects: chiefs, kaids, and witch doctors. …Colonialism secures the services of these loyal servants by paying them a small fortune.

And he also decries those who sell out the oppressed among their people, the workers and peasants and common folks. “To its brutal policy of oppression(the colonial administration) adds a spectacular and judicious combination of détente, divisive maneuvers, and psychological warfare. Here and there it endeavors to revive tribal conflicts, using agents provocateurs engaged in what is known as countersubversion. Colonialism uses two types of indigenous collaborators to achieve its ends. First of all, there are the usual suspects: chiefs, kaids, and witch doctors. …Colonialism secures the services of these loyal servants by paying them a small fortune.

(Also), the lumpenproletariat will always respond to the call to revolt, but if the insurrection thinks it can afford to ignore it, then this famished underclass will pitch itself into the armed struggle and take part in the conflict, this time on the side of the oppressor. …who never misses an opportunity to have the blacks tear at each other’s throats.”

Eduardo Galeano articulates similar, if decidedly more optimistic, perspectives about encounters around the world, but most especially in Latin America. His recent passing leaves a legacy of clear sighted comprehension of factual nuance and underlying dynamics both, for example in regard to the function of latifundia landowners in maintaining semi-feudal, reactionary patterns of land and productive property ownership, an incisive analysis based on real qualities and relationships instead of skin color.

“Even industrialization— coming late and in dependent form, and comfortably coexisting with the latifundia and the structures of inequality— helps to spread unemployment rather than to relieve it; poverty is extended, wealth concentrated in the area where an ever multiplying army of idle hands is available. New factories are built in the privileged poles of development— Sao Paulo, Buenos Aires, Mexico City— but less and less labor is needed. The system did not foresee this small headache, this surplus of people. And the people keep reproducing. They make love with enthusiasm and without precaution. Ever more people are left beside the road, without work in the countryside, where the latifundios reign with their vast extensions of idle land, without work in the city where the machine is king. The system vomits people. North American missionaries sow pills, diaphragms, intrauterine devices, condoms, and marked calendars, but reap children. Latin American children obstinately continue getting born, claiming their natural right to a place in the sun in these magnificent lands which could give to all what is now denied to almost all.”

Today’s dictatorial thug, plied with prostitutes and armaments, turns into tomorrow’s fall guy, while the latifundia, aristocrats, and local propertied classes remain in control and effectively inoculated against the essential step that the workers of their societies have only occasionally embraced, overthrowing their parasitic and conspiratorial imprimatur once and for all. Though Rodney, in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, rails against prejudice and “vicious White racism,” he is clear in his analysis. In none of the cases that he investigates is the race of the oppressors or the color of the oppressed, or vice versa, the deciding factor.

Today’s dictatorial thug, plied with prostitutes and armaments, turns into tomorrow’s fall guy, while the latifundia, aristocrats, and local propertied classes remain in control and effectively inoculated against the essential step that the workers of their societies have only occasionally embraced, overthrowing their parasitic and conspiratorial imprimatur once and for all. Though Rodney, in How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, rails against prejudice and “vicious White racism,” he is clear in his analysis. In none of the cases that he investigates is the race of the oppressors or the color of the oppressed, or vice versa, the deciding factor.

“(Truly), because of lack of engineers, Africa cannot on its own build more roads, bridges, and hydroelectric stations. But that is not a cause of underdevelopment, except in the sense that causes and effects come together and reinforce each other. The fact of the matter is that the most profound reasons for the economic backwardness of a given African nation are not to be found inside that nation. All that we can find inside are the symptoms of underdevelopment and the secondary factors that make for poverty. Mistaken interpretations of the causes of underdevelopment usually stem either from prejudiced thinking or from the error of believing that one can learn the answers by looking inside the underdeveloped economy. The true explanation lies in seeking out the relationship between Africa and certain developed countries and in recognizing that it is a relationship of exploitation.”

Nobel Literary Laureate Wole Soyinka hammers this notion home. “Walter Rodney was no captive intellectual playing to the gallery of local or international radicalism. He was clearly one of the most solidly ideologically situated intellectuals ever to look colonialism and its contemporary heir black opportunism and exploitation in the eye.”

Again, coloration, or race, does not cause or play a significant role in this opportunism and exploitation: these malefactors come in all shades. What turns out to be dispositive, again and again and again and again—and again—are the twin factors of geopolitical strategy, along with its scramble for resources and markets, on the one hand, and the capacity to control and dispose of vast armies of labor and muscle, as well as buckets of cash, on the other hand. Skin color just doesn’t explain either the political economic tangles or the socioeconomic conundrums that capital causes in these struggles and then solves to its own advantage until working people of different colors—can anyone present say Cuba?!—have united to oppose bourgeois overlords.

Most recently as regards both Africom, with the U.S. emphasis on an entire continent, and Ukraine, with the focus on flanking any Eurasian union that sets American finance aside, militarized and belligerent policies and tactics have again been appearing in the guise of free markets and freedom: “We only want to help you be free, free to sell us your commodities at reduced rates while we provide loans and credits that guarantee debt peonage more stringent than what Argentina is battling.” A slightly different plotline spins out in Iran and Southeast Asia, merely to mention a couple of other spots that the United States of America intends to dominate as it barricades the Chinese colossus.

Most recently as regards both Africom, with the U.S. emphasis on an entire continent, and Ukraine, with the focus on flanking any Eurasian union that sets American finance aside, militarized and belligerent policies and tactics have again been appearing in the guise of free markets and freedom: “We only want to help you be free, free to sell us your commodities at reduced rates while we provide loans and credits that guarantee debt peonage more stringent than what Argentina is battling.” A slightly different plotline spins out in Iran and Southeast Asia, merely to mention a couple of other spots that the United States of America intends to dominate as it barricades the Chinese colossus.

Wherever one turns, in any event, literally everywhere on Earth, imperial threads bind up social ties and predatory plutocrats in the service of empire seek to siphon the flow of production and consumption through their elite organizations—banks and conglomerates and corporate behemoths. They care about skin color only when it serves as a motivation or a distraction, either a ‘carrot’ or a ‘stick,’ that helps to lubricate their successful predominance. Those whose station in life requires, if they are to prosper or even live, organizational alliances with other similarly situated citizens would do best to keep this point in mind.

Legacies of Relatively Recent Oppression, Discrimination, Brutality, & Murder

One might liken the present pass to a slow motion chain reaction, in which humans act in similar fashion as concentrated atoms of fissile material. Whether the Uranium originates from Canada or Central Africa makes zero difference, just as the social conflicts of the present, whatever appearances might suggest, do not depend on skin color so much as on deeper historical, geographic, and socioeconomic forces.

Unfortunately, the apparent protracted attainment of a critical mass has probably contributed in lulling people not to worry about the very real potential of crisping in an actual nuclear frying pan, as a result of the volatility of our ongoing social battles. In a sense, we are like pathetic frogs—some green, some yellow, some brown, all the same species and wary of each other as our fluid perches get warmer and warmer—that will not leap from the water that will boil them so long as it heats up slowly enough.

Just as human communities of any coloration long for the same things—decent employment, good schools, comfortable places to live, etc.—so too the differently hued amphibians would have similar needs and, in their froglike ways, hopes. Even as the scientists studying the frogs might separate them by color, or the elites ruling the human roost might divide populations by skin tone, these factors will actually mean nothing in terms of their ultimate fate.

In his Impacts of Science on Society, Bertrand Russell spoke to this issue with a simple and yet lovely parable. “Mankind is in the position of a man climbing a difficult and dangerous precipice, at the summit of which there is a plateau of delicious mountain meadows. With every step that he climbs, his fall, if he does fall, becomes more terrible; with every step his weariness increases and the ascent grows more difficult. At last there is only one more step to be taken, but the climber does not know this, because he cannot see beyond the jutting rocks at his head. His exhaustion is so complete that he wants nothing but rest. If he lets go he will find rest in death. Hope calls: ‘One more effort-perhaps it will be the last effort needed.’ Irony retorts: ‘Silly fellow! Haven’t you been listening to hope all this time, and see where it has landed you.’ Optimism says: ‘While there is life there is hope.’ Pessimism growls: ‘While there is life there is pain.’ Does the exhausted climber make one more effort, or does he let himself sink into the abyss? In a few years those of us who are still alive will know the answer.”

The flashpoints, from which our kind can ‘slip into despair’ and disappear in a heated rush, are legion, though some hotspots named in the section just above rank as likelier possibilities for mass collective suicide than do other places. The conflicts in most of them are possible to view through a lens of ‘race,’ something that half or more of the critiques of U.S. or ‘Western’ policy bring to bear in excoriating the slide toward mayhem and murder. Yet this trope—that ‘racism’ explains why and how we move toward predatory warfare—simply does not hold up.

The Spindoctor has written on Contributoria and elsewhere about the willful ignorance and distorted propaganda that has passed for monopoly mediation about the past few years in Ukraine. While ‘racism’ is simply impossible to apply in this location, even though dynamically and structurally it differs little from possible debacles elsewhere, many analysts do view the confrontations there as potentially lethal in any number of ways, including the possible inducement of multiple Chernobylish meltdowns or the simple escalation of conflict between Russia and the U.S., whose combined thermonuclear arsenals are fully adequate to kill all humans in the world several times over. Helen Caldicott is one of those who warns us.

“The expansion of NATO to Russia’s borders is ‘very, very dangerous,’ Caldicott said. ‘There is no way a war between the United States and Russia could start and not go nuclear. … The United States and Russia have enormous stockpiles of these weapons. Together they have 94 percent of all the 16,300 nuclear weapons in the world.’

We are in a very fallible, very dangerous situation operated by mere mortals,’ she warned. ‘The nuclear weapons, are sitting there, thousands of them. They are ready to be used.’

Caldicott strongly criticized Obama administration policymakers for their actions in forward positioning U.S. and NATO military units in countries of Eastern Europe in response to Russian support of breakaway separatists in the provinces of eastern Ukraine. (A few days ago), the U.S. government announced the deployment of the Ironhorse Brigade, an elite armored cavalry unit of the U.S. Army to the former Soviet republics of Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia, along the historic invasion route from the West to St. Petersburg.

‘Do they really want a nuclear war with Russia?’ she asked. ‘The only war that you can have with Russia is a nuclear war. … You don’t provoke paranoid countries armed with nuclear weapons.’”

The masters-of-the-universe in charge of things in the District of Columbia and Manhattan and elsewhere are certainly not the first ruling class that has believed it could practice rapine and manslaughter without having ever either to pay any recognizable piper or to confront an opponent that will go to the mat. Very similar events happened in 1914, when, without once even wondering about ‘racial’ overtones, all the ‘smart money’ plutocrats publicly insisted, and the ‘leaders’ of unions and socialists also contended, that the carnage of World War One ‘would never happen.’

“The key to preventing war, socialists believed, was to force arbitration through the threat of a general strike. In 1914, their great chance to force arbitration had come, but they had not had time to put their theories into place because events moved with dizzying speed. None of the Brussels delegates ‘suspected that a European war was imminent,’ even though it was just hours away,” and fated to involve all the ‘races-of-man’ in a mad, homicidal melee.

Or perhaps the thought is that ‘containment’ is plausible, not of the forces that empire’s fiendish administrators draw forth in opposition, but of the uproar and outbursts of the nuclear explosions themselves. In such a view, even as imperial fantasies crumble into dust, even as nuclear reactors melt down and spew forth invisible plumes of mass murder, even as people begin to rise in revolution against any further plutocratic plunder, somehow or other the Strangelovian geniuses in command will foreswear the final thrust that delivers the coup d’état to all and sundry all at once. Does that seem like a reasonable scenario for optimism?

Or perhaps the thought is that ‘containment’ is plausible, not of the forces that empire’s fiendish administrators draw forth in opposition, but of the uproar and outbursts of the nuclear explosions themselves. In such a view, even as imperial fantasies crumble into dust, even as nuclear reactors melt down and spew forth invisible plumes of mass murder, even as people begin to rise in revolution against any further plutocratic plunder, somehow or other the Strangelovian geniuses in command will foreswear the final thrust that delivers the coup d’état to all and sundry all at once. Does that seem like a reasonable scenario for optimism?

One might ponder the multiple contingency plans of the United States in ruminating about an answer to the question. As a socialist organization argued about the early-2000’s ‘build-up’ that took place prior to the present ‘build-up,’ “The new nuclear weapons doctrine was drawn up in a secret Pentagon report delivered to Congress in January, and made public by the Los Angeles Times March 10. Seven countries are on the US hit list, including Russia, China, North Korea, Iran, Iraq, Syria and Libya, and the US military would be authorized to use nuclear weapons under a wide range of conditions, including whenever conventional weaponry proved inadequate for Washington’s purposes.”

Six of those polities might lead one to invoke a ‘racial’ explanatory nexus. Russia, obviously, unless we bring Hitler and his ‘hatred of Slavs’ back to the forefront, as the seventh, could not serve as a ‘racial’ case. The upshot is that in these matters of calculating life and death, in which the same propositions and theories are in play as in dealings with Mexico or Haiti or inner city conflicts in North America, ‘race’ is at best foolish as a way to account for things, even though people do so, arguing that ‘attacks on Libya/Iran/North Korea/China are racist’ when the same factors induce such actions as induce a skirmish with Russia, or conceivably with New Zealand for that matter. The journalists from the Fourth International break down how the nations—and ‘races—involved have responded to these games of brinkmanship.

“The governments of the states targeted for nuclear annihilation were naturally unwilling to accept US assurances that the Pentagon nuclear plan was merely a continuation of contingency plans drawn up under the Clinton administration. (No US spokesman has sought to explain the contradiction between the claim that the plan contains ‘nothing new’ and the fact that it was devised in response to the September 11 terrorist attacks).

China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Sun Yuxi stressed that China and the United States had agreed not to target each other with nuclear weapons. ‘Like many other countries, China is deeply shocked with the content of this report,’ he declared. ‘The US side has a responsibility to explain this.’

A leading Russian legislator, Dmitri Rogozin, declared that the US government seemed to have lost touch with reality since September 11. ‘They’ve brought out a big stick—a nuclear stick that is supposed to scare us and put us in our place,’ he told NTV television. Russian Foreign Minister Igor Ivanov called the reports destabilizing and said that top-level Bush administration officials had an obligation to ‘make things clear and calm the international community, convincing it that the United States does not have such plans.’”

Whatever the case may be, students of human existence far wiser and more knowledgeable than any mere Spindoctor have long warned about these sorts of ‘slippery slopes,’ which can exist as much more than logical fallacies when the necessary prerequisites are, so to say, fully requited. Many of these wiser heads, though they served as ‘race leaders,’ in fact often focus passionately on these matters of geopolitics and imperial imprimatur.

Martin Luther King, who died interestingly enough when his work turned fully against the Vietnam war and in favor of explicit, multihued working class organization in Memphis, warned presciently, in essence, that ‘the bombs that we detonate in Southeast Asia will explode, soon enough, in our own living rooms.’ He had wedded his career to discussions of racial rights, and yet in these conversations, this way of thinking very definitely receded into the background, since the equities in play applied to people of all colors, even if disparate negative impacts continued disproportionately to affect darker-skinned minorities.

Martin Luther King, who died interestingly enough when his work turned fully against the Vietnam war and in favor of explicit, multihued working class organization in Memphis, warned presciently, in essence, that ‘the bombs that we detonate in Southeast Asia will explode, soon enough, in our own living rooms.’ He had wedded his career to discussions of racial rights, and yet in these conversations, this way of thinking very definitely receded into the background, since the equities in play applied to people of all colors, even if disparate negative impacts continued disproportionately to affect darker-skinned minorities.

Moreover, no less than Nelson Mandela spent much of his energy in his final years fighting to eliminate nuclear war from the human prospect, doing work in which he often made zero mention of race or racism. He presented an impassioned plea at the United Nations on the Autumnal Equinox in 1998 along these lines, begging for the elimination of nuclear annihilation as a political tactic, and tying this entreaty to a general analysis of social justice: “The very right to be human is denied everyday to hundreds of millions of people as a result of poverty, the unavailability of basic necessities such as food, jobs, water and shelter, education, health care and a healthy environment.

The failure to achieve the vision contained in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights finds dramatic expression in the contrast between wealth and poverty which characterises the divide between the countries of the North and the countries of the South and within individual countries in all hemispheres.

It is made especially poignant and challenging by the fact that this coexistence of wealth and poverty, the perpetuation of the practice of the resolution of inter and intra-state conflicts by war and the denial of the democratic right of many across the world, all result from the acts of commission and omission particularly by those who occupy positions of leadership in politics, in the economy and in other spheres of human activity.

What I am trying to say is that all these social ills which constitute an offence against the Universal Declaration of Human Rights are not a pre-ordained result of the forces of nature or the product of a curse of the deities.

They are the consequence of decisions which men and women take or refuse to take, all of whom will not hesitate to pledge their devoted support for the vision conveyed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

They are the consequence of decisions which men and women take or refuse to take, all of whom will not hesitate to pledge their devoted support for the vision conveyed in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

This Declaration was proclaimed as Universal precisely because the founders of this Organisation and the nations of the world who joined hands to fight the scourge of fascism, including many who still had to achieve their own emancipation, understood this clearly—that our human world was an interdependent whole.” The only race here, as Mandela reminds those who will listen intently, is the human race, which is both our mutual collectivity as a species and our long run toward something akin to human thriving and survival.

Color & Convenience in Selecting Schemes of ‘Divide & Conquer’

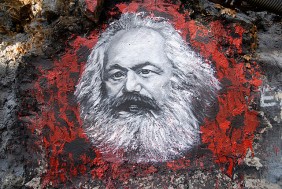

Karl Marx famously implored unity among working people. The regular failure of this evident directive notwithstanding, one might reasonably posit that only such an eventuality can result in a historical transformation that makes something other than the decimation or elimination of any human future plausible.

Imbibing argumentation in this manner, one cannot help but wonder if the seemingly random and yet immanent outgrowth of ‘race’ and the legions of other grasping individualistic ‘identities’ are not so much natural as cultivated, not so much inherent as manipulated. After all, if a fundamental unity, at the same time organic and social, binds people and their fates together, as if some optimistic musical production were in fact actual, then the lines from “Solidarity Forever” would prove unstoppable.

“In our hands we hold a power greater than their hoarded gold,

Greater than the might of armies magnified a thousand-fold;

We can bring to birth a new world from the ashes of the old,

For our union makes us strong.”

In the Gilbert and Sullivan staging of such a drama, the entrepreneur and the banker and the industrialist and the field-marshal in chorus would shudder and shout, “Heaven forfend!!” They would scurry about, their faces purpled and their hearts aflutter, as they parlayed together to imagine, and then impose, tricks to distance from each other all of their inferiors, in so doing crushing any such prospective union, let alone a real, society-wide class conscious unification.

In this vein, by far the most utilitarian mechanisms for pushing people apart have to include skin-color, language, cultural background, and religious faith. Thus, that an ongoing conflation of all of these factors as racial has been occurring since at least the 1990’s is noteworthy, not to mention profoundly troubling. While essentially innumerable examples of such happenings would be possible in a still-longer investigation, here we might peer at a few cases and know that plentiful additional data is available.

A first sampling examines a recent post in the wide-ranging online periodical, CounterCurrents, which speaks of how divide and conquer schemes in contemporary Gujarat have imposed color separation on Hindu and Muslim students. The predictable outcomes of this policy choice, alienation and tension, are none the less hideous for their plain inevitability.

This story’s articulation details how, following fiscally manipulated and politically enforced ‘concentration’ of Islamic residents, ghettoized Muslim academies are without exception dictating that students wear green uniforms, while Hindu pupils don saffron garb. “What do we do in the face of a situation where the schools are choosing uniforms according to the religion of the children, and how come the percentage of children is overwhelmingly Muslim or Hindu in particular areas? This is due to physical segregation and is contrary to the spirit of communal harmony and the values ingrained in the basics of Indian Constitution, the spirit of Fraternity.

One has to counter the myths, biases and prejudices about the ‘other community’ as these stereotypes form the base of communal violence, which in turn paves the way for segregation and ghettoization which further leads to ‘cultural demarcation’, the way these two schools show. What type of future society(will result), we can envisage with such stereotypes entering into our education system. (At the very least), (t)he physical and emotional divides which are coming up are detrimental to the unity of the nation as a whole.”

The author’s final paragraph harks back to the very year in which Britain’s imperial unraveling consciously surrounded Hindi India with Islamic East and West Pakistan. “The communal violence has brought to (the) fore the religious identity without bring(ing) in the values of tolerance and acceptance for the ‘other’. I remember having watched V.Shantarams’ 1946 classic, Padosi (neighbor), and leaving the theatre with moist eyes, wondering whether Hindus and Muslims can ever live like this again, whether the composite culture which India inherits has any chance of survival in the prevalent divisive political scenario!”

U.S. prisons, meanwhile, the seamier and more violent lock-ups especially, offer up a second set of instances, that in general circumscribe an entire universe in which strictly coded and enforced ‘racial segregation’ has become the default, a clearly illegal outcome in terms of equal protection and other such Constitutional fantasies, but a result that authorities permit ostensibly for the safety and security of both the degraded and dehumanized prisoners themselves, often in a state of semi-permanent lockdown, and for the benefit of the largely White population of prison guards. Recent California legislation to rein in such practices notwithstanding, they remain the cutting edge of current incarceration practice in maximum-security facilities. Not that such practice is illogical, quite the contrary, in settings in which White-supremacy is a dominant ideology among many Anglo workers, nationalist separatism and self-protection holds sway among particularly some Islamic Black cohorts, and clearly racialist, Spanish-speaking gangs have emerged among Hispanic prisoners, such ironclad division appears immutable.

A young scholar from Florida makes a chilling case that such developments are corporate policy, the imprimatur of imperial capital writ large. “The aim of this analysis is to uncover the reasons why crime legislation became progressively more punitive, reaction to African Americans gains in post-Civil Rights more hostile, and the manifold ways in which these phenomena drive the expansion of the prison system and its increasing privatization. In the process of this expansion, a racial caste system which oppresses young African Americans and people of color has become recast and entrenched. Specifically, I offer the notion that in the last three decades, punitive crime legislation focused on African Americans and served to deal with labor needs and racial conflict with harsher penal legislation; in doing so, it depoliticized race, institutionalized racial practices and served the interest of private prison businesses in new and oppressive ways.”